You are reading the work-in-progress first edition of Causal Inference in R. This chapter has its foundations written but is still undergoing changes.

11 Fitting the weighted outcome model

11.1 Using matched data sets

When fitting an outcome model on matched data sets, we can simply subset the original data to only those who were matched and then fit a model on these data as we would otherwise. For example, re-performing the matching as we did in Section 8.2, we can extract the matched observations in a dataset called matched_data as follows.

library(broom)

library(touringplans)

library(MatchIt)

seven_dwarfs_9 <- seven_dwarfs_train_2018 |>

filter(wait_hour == 9)

m <- matchit(

park_extra_magic_morning ~ park_ticket_season + park_close + park_temperature_high,

data = seven_dwarfs_9

)

matched_data <- get_matches(m)We can then fit the outcome model on this data. For this analysis, we are interested in the impact of extra magic morning hours on the average posted wait time between 9 and 10am. The linear model below will estimate this in the matched cohort.

lm(wait_minutes_posted_avg ~ park_extra_magic_morning, data = matched_data) |>

tidy(conf.int = TRUE)# A tibble: 2 × 7

term estimate std.error statistic p.value conf.low

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 (Inte… 67.0 2.37 28.3 1.94e-54 62.3

2 park_… 7.87 3.35 2.35 2.04e- 2 1.24

# ℹ 1 more variable: conf.high <dbl>Recall that by default MatchIt estimates an average treatment effect among the treated. This means among days that have extra magic hours, the expected impact of having extra magic hours on the average posted wait time between 9 and 10am is 7.9 minutes (95% CI: 1.2-14.5).

11.2 Using weights in outcome models

Now let’s use propensity score weights to estimate this same estimand. We will use the ATT weights so the analysis matches that for matching above.

library(propensity)

propensity_model <- glm(

park_extra_magic_morning ~ park_ticket_season + park_close + park_temperature_high,

data = seven_dwarfs_9,

family = binomial()

)

seven_dwarfs_9_with_ps <- propensity_model |>

augment(type.predict = "response", data = seven_dwarfs_9)

seven_dwarfs_9_with_wt <- seven_dwarfs_9_with_ps |>

mutate(w_att = wt_att(.fitted, park_extra_magic_morning))We can fit a weighted outcome model by using the weights argument.

lm(

wait_minutes_posted_avg ~ park_extra_magic_morning,

data = seven_dwarfs_9_with_wt,

weights = w_att

) |>

tidy()# A tibble: 2 × 5

term estimate std.error statistic p.value

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 (Intercept) 68.7 1.45 47.3 1.69e-154

2 park_extra_ma… 6.23 2.05 3.03 2.62e- 3Using weighting, we estimate that among days that have extra magic hours, the expected impact of having extra magic hours on the average posted wait time between 9 and 10am is 6.2 minutes. While this approach will get us the desired estimate for the point estimate, the default output using the lm function for the uncertainty (the standard errors and confidence intervals) are not correct.

group_by() and summarize(), revisted

For this simple example, the weighted outcome model is equivalent to taking the difference in the weighted means.

wt_means <- seven_dwarfs_9_with_wt |>

group_by(park_extra_magic_morning) |>

summarize(average_wait = weighted.mean(wait_minutes_posted_avg, w = w_att))Warning: There were 2 warnings in `summarize()`.

The first warning was:

ℹ In argument: `average_wait =

weighted.mean(wait_minutes_posted_avg, w = w_att)`.

ℹ In group 1: `park_extra_magic_morning = 0`.

Caused by warning in `vec_ptype2.psw.double()`:

! Converting psw to numeric

ℹ Class-specific attributes and metadata have been

dropped

ℹ Use explicit casting to numeric to avoid this

warning

ℹ Run `dplyr::last_dplyr_warnings()` to see the 1

remaining warning.wt_means# A tibble: 2 × 2

park_extra_magic_morning average_wait

<dbl> <dbl>

1 0 68.7

2 1 74.9The difference is 6.23, the same as the weighted outcome model.

The weighted population is a psuedo-population where there is no confounding by the variables in the propensity score. Philosophically and practically, we can make calculations with the data from this population. Causal inference with group_by() and summarize() works just fine now, since we’ve already accounted for confounding in the weights.

11.3 Estimating uncertainty

There are three ways to estimate the uncertainty:

- A bootstrap

- A sandwich estimator that only takes into account the outcome model

- A sandwich estimator that takes into account the propensity score model

The first option can be computationally intensive, but should get you the correct estimates. The second option is computationally the easiest, but tends to overestimate the variability. There are not many current solutions in R (aside from coding it up yourself) for the third; however, the {PSW} package will do this.

11.3.1 The bootstrap

- Create a function to run your analysis once on a sample of your data

fit_ipw <- function(.split, ...) {

# get bootstrapped data frame

.df <- as.data.frame(.split)

# fit propensity score model

propensity_model <- glm(

park_extra_magic_morning ~ park_ticket_season + park_close + park_temperature_high,

data = seven_dwarfs_9,

family = binomial()

)

# calculate inverse probability weights

.df <- propensity_model |>

augment(type.predict = "response", data = .df) |>

mutate(wts = wt_att(

.fitted,

park_extra_magic_morning,

exposure_type = "binary"

))

# fit correctly bootstrapped ipw model

lm(

wait_minutes_posted_avg ~ park_extra_magic_morning,

data = .df,

weights = wts

) |>

tidy()

}- Use {rsample} to bootstrap our causal effect

library(rsample)

# fit ipw model to bootstrapped samples

bootstrapped_seven_dwarfs <- bootstraps(

seven_dwarfs_9,

times = 1000,

apparent = TRUE

)

ipw_results <- bootstrapped_seven_dwarfs |>

mutate(boot_fits = map(splits, fit_ipw))

ipw_results# Bootstrap sampling with apparent sample

# A tibble: 1,001 × 3

splits id boot_fits

<list> <chr> <list>

1 <split [354/130]> Bootstrap0001 <tibble [2 × 5]>

2 <split [354/128]> Bootstrap0002 <tibble [2 × 5]>

3 <split [354/119]> Bootstrap0003 <tibble [2 × 5]>

4 <split [354/134]> Bootstrap0004 <tibble [2 × 5]>

5 <split [354/130]> Bootstrap0005 <tibble [2 × 5]>

6 <split [354/127]> Bootstrap0006 <tibble [2 × 5]>

7 <split [354/124]> Bootstrap0007 <tibble [2 × 5]>

8 <split [354/135]> Bootstrap0008 <tibble [2 × 5]>

9 <split [354/129]> Bootstrap0009 <tibble [2 × 5]>

10 <split [354/132]> Bootstrap0010 <tibble [2 × 5]>

# ℹ 991 more rowsLet’s look at the results.

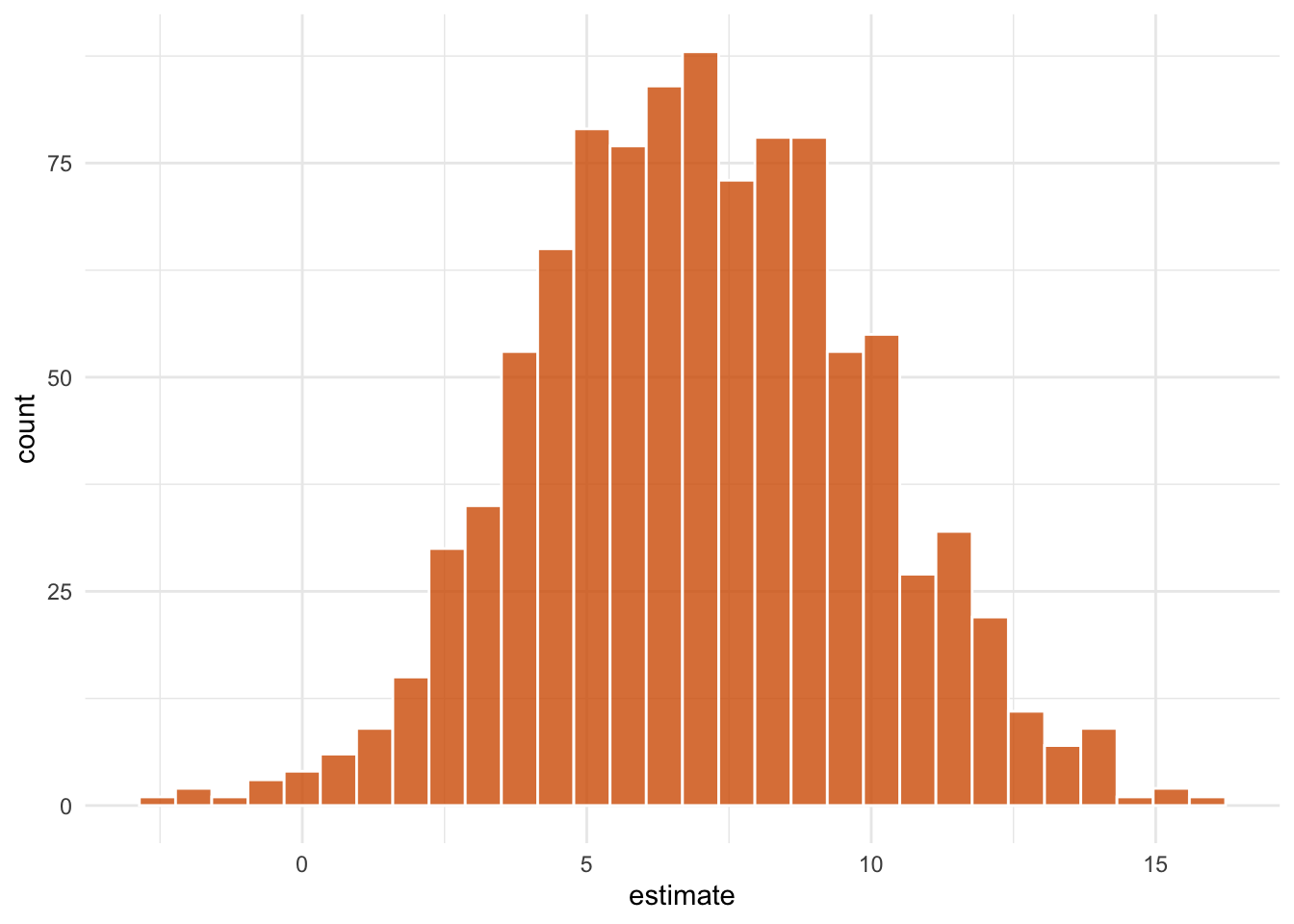

ipw_results |>

mutate(

estimate = map_dbl(

boot_fits,

\(.fit) .fit |>

filter(term == "park_extra_magic_morning") |>

pull(estimate)

)

) |>

ggplot(aes(estimate)) +

geom_histogram(bins = 30, fill = "#D55E00FF", color = "white", alpha = 0.8) +

theme_minimal()

- Pull out the causal effect

# get t-based CIs

boot_estimate <- int_t(ipw_results, boot_fits) |>

filter(term == "park_extra_magic_morning")

boot_estimate# A tibble: 1 × 6

term .lower .estimate .upper .alpha .method

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr>

1 park_extra_ma… 0.200 6.95 11.5 0.05 studen…We estimate that among days that have extra magic hours, the expected impact of having extra magic hours on the average posted wait time between 9 and 10am is 7 minutes, 95% CI (0.2, 11.5).

11.3.2 The outcome model sandwich

There are two ways to get the sandwich estimator. The first is to use the same weighted outcome model as above along with the sandwich package. Using the sandwich function, we can get the robust estimate for the variance for the parameter of interest, as shown below.

library(sandwich)

weighted_mod <- lm(

wait_minutes_posted_avg ~ park_extra_magic_morning,

data = seven_dwarfs_9_with_wt,

weights = w_att

)

sandwich(weighted_mod) (Intercept)

(Intercept) 1.488

park_extra_magic_morning -1.488

park_extra_magic_morning

(Intercept) -1.488

park_extra_magic_morning 8.727Here, our robust variance estimate is 8.727. We can then use this to construct a robust confidence interval.

robust_var <- sandwich(weighted_mod)[2, 2]

point_est <- coef(weighted_mod)[2]

lb <- point_est - 1.96 * sqrt(robust_var)

ub <- point_est + 1.96 * sqrt(robust_var)

lbpark_extra_magic_morning

0.4383 ubpark_extra_magic_morning

12.02 We estimate that among days that have extra magic hours, the expected impact of having extra magic hours on the average posted wait time between 9 and 10am is 6.2 minutes, 95% CI (0.4, 12).

Alternatively, we could fit the model using the survey package. To do this, we need to create a design object, like we did when fitting weighted tables.

Then we can use svyglm to fit the outcome model.

# A tibble: 2 × 7

term estimate std.error statistic p.value conf.low

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 (Int… 68.7 1.22 56.2 6.14e-178 66.3

2 park… 6.23 2.96 2.11 3.60e- 2 0.410

# ℹ 1 more variable: conf.high <dbl>11.3.3 Sandwich estimator that takes into account the propensity score model

The correct sandwich estimator will also take into account the uncertainty in estimating the propensity score model. ipw() will allow us to do this. To do so, we need to provide both the propensity score model and the outcome model.

results <- ipw(propensity_model, weighted_mod)

resultsInverse Probability Weight Estimator

Estimand: ATT

Propensity Score Model:

Call: glm(formula = park_extra_magic_morning ~ park_ticket_season +

park_close + park_temperature_high, family = binomial(),

data = seven_dwarfs_9)

Outcome Model:

Call: lm(formula = wait_minutes_posted_avg ~ park_extra_magic_morning,

data = seven_dwarfs_9_with_wt, weights = w_att)

Estimates:

estimate std.err z ci.lower ci.upper

diff 6.23 2.34 2.66 1.64 10.8

conf.level p.value

diff 0.95 0.0078 **

---

Signif. codes:

0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1We can also collect the results in a data frame.

results |>

as.data.frame() effect estimate std.err z ci.lower ci.upper

1 diff 6.228 2.339 2.663 1.644 10.81

conf.level p.value

1 0.95 0.00775311.4 Binary outcomes: Risk ratio, risk difference, and odds ratio

In the example we’ve taken up, the outcome, posted wait times, is continuous. Using weighted linear regression, the ATE and friends are calculated as a difference in means. A difference in means is a valuable effect to estimate, but it’s not the only one. Let’s say we use ATT weights and weight an outcome regression to calculate the relative change in posted wait time. The relative change is still a treatment effect among the treated, but it’s on a relative scale. The important part is that the weights allow us to average over the covariates of the treated for whichever specific estimand we’re trying to estimate. Sometimes, when people say something like “the average treatment effect,” they are talking about a difference in mean outcomes among the whole sample, so it’s good to be specific.

For binary outcomes, we have three standard options: the risk ratio, risk difference, and odds ratio. In the case of a binary outcome, we calculate average probabilities for each treatment group. Let’s call these p_untreated and p_treated. When we’re working with these probabilities, calculating the risk difference and risk ratio is simple:

-

Risk difference:

p_treated - p_untreated -

Risk ratio:

p_treated / p_untreated

By “risk”, we mean the risk of an outcome. That assumes the outcome is negative, like developing a disease. Sometimes, you’ll hear these described as the “response ratio” or “response difference”. A more general way to think about these is as the difference in or ratio of the probabilities of the outcome.

The odds for a probability is calculated as p / (1 - p), so the odds ratio is:

-

Odds ratio:

(p_treated / (1 - p_treated)) / (p_untreated / (1 - p_untreated))

When outcomes are rare, (1 - p) approaches 1, and odds ratios approximate risk ratios. The rarer the outcome, the closer the approximation.

One feature of the logistic regression model is that the coefficients are log-odds ratios, so exponentiating them produces odds ratios. However, when using logistic regression, you can also work with predicted probabilities to calculate risk differences and ratios, as we’ll see in Chapter 13.

Just like with continuous outcomes, we can target each of these estimands for a different subset of the population, e.g., the risk ratio among the untreated, the odds ratio among the evenly matchable, and so on.

These options also extend to categorical outcomes. There are different ways of organizing them depending on the nature of the categorical variables. An effect that’s commonly estimated for non-ordinal categorical variables is a series of odds ratios with one level of the outcome serving as the reference level (e.g., an OR for 1 vs. 2 and 1 vs. 3 and so on). Multinomial regression models, such as nnet::multinom(), can produce these log-odds ratios as coefficients, an extension of logistic regression. For ordinal outcomes, ordinal logistic regression like MASS::polr() calculates a series of log-odds ratios that compare each previous value of the outcome. Like logistic regression, you are not limited to odds ratios with these extensions, as you can work with the predicted probabilities of each category to calculate the effect you’re interested in.

Case-control studies are a typical design in epidemiology where participants are sampled by outcome status (Schlesselman 1982). Cases with the outcome are recruited, and controls are sampled from the population from which the cases come. These types of studies are used when outcomes are rare. They can also be faster and cheaper than studies that follow people from the time of exposure.

Because of how sampling happens in case-control studies, you don’t have baseline risk because you don’t have all the individuals who did not have the outcome. Interestingly, you can still recover the odds ratio. When outcomes are rare, odds ratios approximate risk ratios. You cannot, however, calculate the risk difference.

11.4.1 Absolute and relative measures

Absolute measures, such as risk differences, and relative measures, such as the risk and odds ratios, offer different perspectives on the treatment effect. Depending on the baseline probability of the outcome, absolute and relative measures might lead you to different conclusions.

Consider a rare outcome with a baseline probability of 0.0001, a rate of 1 event per 10,000 observations. That’s the probability for the unexposed. Let’s say the exposed have a probability of the outcome of 0.0008. That’s 8 times greater than the unexposed, a substantial relative effect. But it’s only 0.0007 on the absolute scale.

Now, consider a more common outcome with a baseline probability of 0.20. The exposed group has a probability of the outcome of 0.40. Now, the relative risk is 2, while the risk difference is 0.20. Although the relative effect is much smaller, it creates more outcome events because the outcome is more prevalent.

The effect of smoking on health is an excellent example of this. As we know, smoking drastically increases the relative risk of lung cancer. But lung cancer is a pretty rare disease. Smoking also increases the risk of heart disease, although the relative effect is not nearly as high as lung cancer. However, heart disease is much more prevalent. More people die of smoking-related heart disease than they do of lung cancer because of the absolute change in risk. Both the absolute and relative perspectives are valid.

Another perspective on the difference in probabilities is the number needed to treat (NNT) measure. It’s simply the inverse of the risk difference, and it represents the number of exposed individuals needed to prevent or create one outcome.

Consider a product for sale with a baseline purchase probability of 5%, which means that 5 in 100 people will buy this product. A marketing team creates an ad, and those who see the ad have a probability of 7% to buy the product. The absolute difference in probabilities of buying the product is 0.02, and so 1 / 0.02 = 50 people need to see the ad to increase the number of purchases by one.

The NNT is an imperfect measure because of its simplicity, but it offers another perspective on what the treatment effect actually means in practice.

11.4.2 Non-collapsibility

Odds ratios are convenient because of their connection to logistic regression. They also have a peculiar quality: they are non-collapsible. Non-collapsibility means that, when you compare odds ratios in the whole sample (marginal) versus among subgroups (conditional), the marginal odds ratio is not a weighted average of the conditional odds ratio (Didelez and Stensrud 2021; Greenland 2021a, 2021b). This is not a property that, for instance, the risk ratio has. Let’s look at an example.

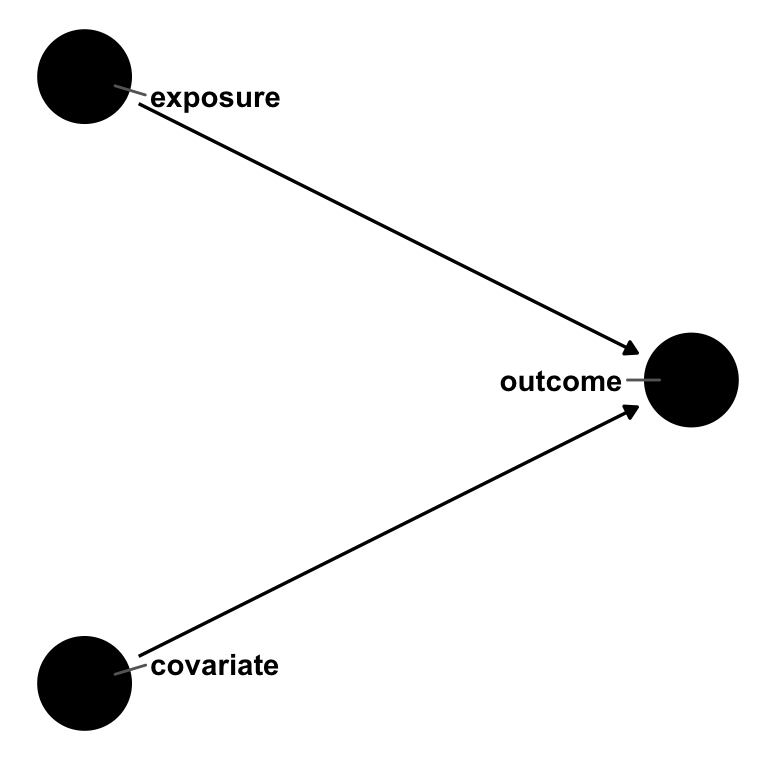

Say we have an outcome, an exposure, and a covariate. exposure causes outcome, as does covariate1. But covariate does not cause exposure; it’s not a confounder. In other words, the effect estimate of exposure on outcome should be the same whether or not we account for covariate.

Code

library(ggdag)

dagify(

outcome ~ exposure + covariate,

coords = time_ordered_coords()

) |>

ggdag(use_text = FALSE) +

geom_dag_text_repel(aes(label = name), box.padding = 1.8, direction = "x") +

theme_dag()

outcome, exposure, and covariate. exposure and covariate both cause outcome, but there is no relationship between exposure and covariate. In a logistic regression, the odds ratio for exposure will be non-collapsible over strata of covariate.

Let’s simulate this.

First, let’s look at the relationship between exposure and outcome among everyone.

table(exposure, outcome) outcome

exposure 0 1

0 2036 3021

1 1115 3828We can calculate the odds ratio using this frequency table: ((3828 * 2036) / (3021 * 1115)) = 2.31.

This odds ratio is the same result we get with logistic regression when we exponentiate the results.

# A tibble: 2 × 5

term estimate std.error statistic p.value

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 (Intercept) 1.48 0.0287 13.8 4.33e-43

2 exposure 2.31 0.0445 18.9 2.87e-79This is a little off from the simulation model coefficient of exp(1). We get closer when we add in covariate.

# A tibble: 3 × 5

term estimate std.error statistic p.value

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 (Intercept) 0.614 0.0378 -12.9 6.07e- 38

2 exposure 2.78 0.0493 20.7 1.33e- 95

3 covariate 7.39 0.0529 37.8 1.04e-312covariate is not a confounder, so by rights, it shouldn’t impact the effect estimate for exposure. Let’s look at the conditional odds ratios by covariate.

table(exposure, outcome, covariate), , covariate = 0

outcome

exposure 0 1

0 1572 986

1 951 1589

, , covariate = 1

outcome

exposure 0 1

0 464 2035

1 164 2239The odds ratio for those with covariate = 0 is 2.66. For those with covariate = 1, it’s 3.11. The marginal odds ratio, 2.31, is smaller than both of these!

The marginal risk ratio is 1.3. The risk ratio for those with covariate = 0 is 1.62. For those with covariate = 1, it’s 1.14. In this case, the marginal risk ratio is a weighted average collapsible over the strata of covariate (Huitfeldt, Stensrud, and Suzuki 2019).

It’s tempting to think you need to include covariate since the odds ratio changes when you add it in, and it’s closer to the model coefficient from the simulation. An important detail here is that non-collapsibility is not bias. Some authors describe it as omitted variable bias, but the marginal and conditional odds ratios are both correct because covariate is not a confounder. They are simply different estimands. The conditional odds ratio is the OR conditional on covariate. To meaningfully compare it to other odds ratios, those also need to condition on covariate. Non-collapsibility is a numerical property of odds; rather than creating bias, it creates a slightly more nuanced interpretation. The exact way non-collapsibility behaves also depends on whether the data-generating mechanism occurs on the additive or multiplicative scale; on the multiplicative scale (as in our simulation), removing a variable strongly related to the outcome changes the effect estimate, while on the additive scale, adding a variable strongly related to the outcome changes the effect, albeit on a smaller scale (Whitcomb and Naimi 2020). Instead of worrying about which version of the odds ratio is right, we recommend focusing on confounders, which are necessary for unbiased estimates, and predictors of the outcome, which are helpful for variance reduction.

Much ink has been spilled about the odds ratio versus the risk ratio and the relative versus absolute scale. We suggest that, for binary outcomes, you present all three measures (the odds ratio, the risk ratio, and the risk difference) together with the baseline probability of the outcome. Each offers a different perspective on the causal effect. Be careful to interpret them with regard to the treatment group that you’ve included in your estimate. For example, the average risk difference calculated with ATT weights is the average risk difference among the treated.

The linear probability model is another common way to estimate treatment effects for binary outcomes. The linear probability model is standard in econometrics and other fields. It’s just OLS, although researchers often use a robust standard error because of heterogeneity in the variance of the residuals. The result is the risk difference, a collapsible measure.

lm(outcome ~ exposure)

Call:

lm(formula = outcome ~ exposure)

Coefficients:

(Intercept) exposure

0.597 0.177 The linear probability model is a handy way to model the relationship on the additive scale. However, it comes with a significant hiccup: logistic regression is bounded by 0 and 1, while OLS is not. That means that individual predictions may be less than 0 or more than 1, impossible values for probabilities.

We’ll see an alternative method for calculating risk differences with logistic regression in Chapter 13.

If there were no relationship between

exposureandoutcome, the relationship between the two would be null, and the odds ratio would be collapsible regardless of the presence or absence ofcovariate.↩︎